Coastal live oak - Quercus agrifolia is an evergreen (always has leaves) oak - is the most commonly observed oak in our local mountains and namesake of the “oak woodland” community. Without too much trouble you will find it in canyons, near creeks and in the shaded area of nearly every kind of plant community. This native tree has adapted to a coastal climate and can be found within 60 miles of the coast up to 5,000 feet. Battle-scarred oaks have inspired artists, philosophers and casual viewers alike for generations. Today, their existence is threatened by a warming climate, drought, fire, disease and urbanization. Can we make changes to save them?

Basic Facts

| Common Name(s): | Coastal Live Oak |

| Scientific Name: | Quercus agrifolia |

| Family: | Fagaceae (Beech) |

| Plant Type: | Tree |

| Size: | 20 to 50 feet high |

| Habitat: | open woodlands |

| Blooms: | February to May |

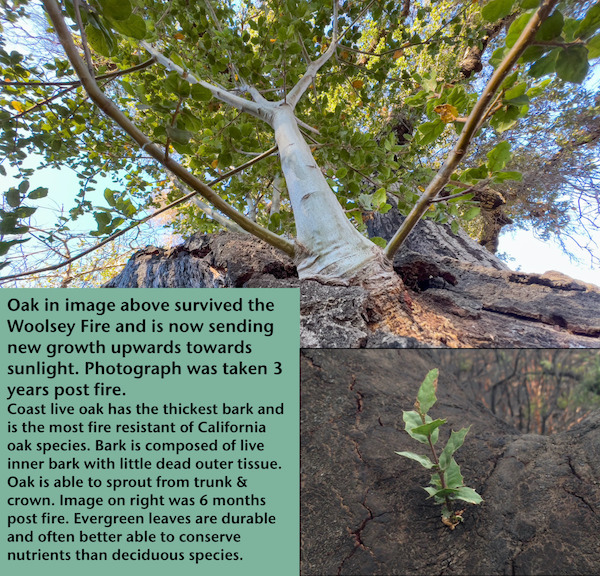

| Fire Response: | sprout from crown and trunk |

Links/Sources:

General Description

These majestic trees can live three centuries, reach heights of 30 to 75 feet, form crowns that can extend 130 feet across and can be 9 to 12 feet in girth - creating a distinct and charismatic profile in the Santa Monica Mountains. The direction the limbs grow seems unpredictable - sometimes growing downwards, even to the point that they touch the ground. A tap root is initially sent down to secure water and the tree. Eventually, horizontal root branches take over the task of securing water.

Coastal live oaks have tough 'leathery' evergreen leaves that protect against herbivory and are mostly convex (cup-like). This 'cupping' shape is believed to collect dew and mist, which would allow the tree to survive years with limited rainfall. Leaves are dark green, oval, ¾ to 4 inches long and ½ -1 1/2 inches wide - leaf texture and shape are similar to holly. Leaves vary on the same tree - areas with lots of sun are often different than areas with more limited light. Every part of the tree is highly adapted to maximize its ability to gather water, light and nutrients from the environment. Leaves that receive the most sunlight exposure tend to be smaller and thicker, with extra layers of photosynthetic cells to capture sunlight. Where there is less light, leaves tend to be thinner, wider, and flatter, with only one layer of photosynthetic cells. When the tree is young the leaves feel rougher and spinier to discourage animals from eating them.

Young trees have smooth gray bark and as the trees mature, furrows develop in the bark giving the tree a distinctive appearance - kind of like gray hair and wrinkles makes us older folk, look - older.

Important Resource for the Chumash

Coast live oaks are capable of producing several hundred pounds of acorns per year. This availability, hard work and some human ingenuity meant that acorns were a major food source for the indigenous peoples of California. For more than 5,000 years the Chumash harvested acorns and dried them in the sun. Once dried, acorns were pounded into a flour and then prepared for consumption by a process called leaching, which removes the bitter, tannic acids. Once properly leached, the acorn flour was mixed with more water and heated into a soup or mush. One source states that the Chumash preferred acorns from coast live oak over the acorns of valley oak [Jan Timbrook "Chumash Ethnobotany" p159] and another states they were valued and often mixed with acorns of other species [M. Kat Anderson "Tending the Wild" p174]. All parts of the oak tree had a use, from medicine to basketry to toys and even musical instruments. Valley oak acorns are the largest of the California native oaks - nearly two inches in length.

Late summer, when the acorns were mature enough they were collected with some stored in primitive granaries Unshelled acorns left outside spoiled quicker than those stored in baskets out of the elements. Preparing acorns for consumption, native people would grind the seeds into powder/flour. A mortar and metate was used to break up the acorn seeds. Tannins were then leached out by soaking in water and changing the water daily for several days. This step improves the taste of the acorns. After grinding, leaching and drying, the acorn meal could be mixed with water and baked into a bread or cake or an acorn gruel. Acorn powder was sometimes toasted and brewed with water to create a flavored beverage. Acorn paste was also used as a sunscreen.

Oak bark was the preferred firewood and made long lasting coals that could used to fire pottery and when buried, could be used the next morning to kindle a fire. Hot coals were used to shape hair after being cut with a knife. Medicines and potions were also made from bark.

Oaks- Essential For Food & Habitat

Oak communities are an important habitat for wildlife, giving a home for nesting birds and food for birds, insects, animals, and even other plants. Butterflies, moths and wasps also depend on oaks for forage and nesting. The Sister butterfly is one such butterfly that depend on coastal live oak for laying eggs and feeding its young. The California Oak Moth aka the California Oak Worm is known for sporadic explosive population growth spurts that create caterpillars that can defoliate an oak tree. Oak trees are resilient so this does not kill the tree but it certainly does not help. Not all of these caterpillars will become moths and instead provide meals for hungry birds. Squirrels, scrub jays, acorn woodpeckers, wood rats and deer eat the acorns. A complete list of creatures dependent on oaks is available from the California Oak Organization - Read Lots More!

Nature plays the percentages: Perhaps 95% of cached acorns will be eaten, the remaining acorns have a higher survival rate than uncached acorns because they’ve been placed in protected locations.

Oak trees serve as the host to the larvae of various parasitic wasps. The apple gall - true to its namesake - is round and varies in color from green to shades of red and finally to brown as it matures; is the home of the California gall wasp, Andricus quercuscalifornicus. This wasp produces eggs without mating and lives for approximately a week after emerging from the gall. Eggs are deposited onto the plant's stems. In the spring, the eggs hatch and as they feed, they release a chemical that causes the gall to swell over a two-month period. The gall provides the appearance of security from predators. However, these galls and the inhabitants inside are a source of food for caterpillars, squirrels, birds and larger wasps.

Plants that are commonly seen in coast live oak communities include bay laurel, toyon, and poison oak.

Coastal Live Oak Traits

Acorns cups have thin, flat scales that resemble roofing shingles (see included image). The acorns mature quickly (compared to other oaks) in one year. The underside of the leaf often has fine hairs in the leafs's midsection. The leaves curl inward and as the schoolkids say "it looks like a boat".

Odds & Ends: On average, trees have high acorn production (referred to as mast years) every 3 to 5 years. Flowering from February to April the fruits (acorns) mature late summer.

The "live" part of the name is a reference to the evergreen leaves - incidentally, these leaves are dropped in the spring when new leaves are produced.

Oaks often hybridize with other oak species, complicating identification.

Coastal live oak is wind-pollinated, has both male and female flowers growing on the same tree. The male flowers form tight hanging clusters of small flowers called catkins. The female flowers are more of a challenge to find - they are definitely inconspicuous. I will post images of them as soon as I find them.

The fruit is a nut that we call an acorn. Look closely and you can see that the acorn cap/cup is a modified involucre with overlapping bracts! I encourage you to take the time to look at an oak tree and see if you can find the items this page will be describing.

Friday Fun Fact: encino and roble are two Spanish words that describe oaks. Encino refers to the evergreen species (coast live oak) and roble refers to the deciduous species (valley oak).

Name Origin

Quercus: the classical Latin name for the oak from Roman times, interestingly no certain derivation for the name, possibly from the Celtic quer, "fine," and cuez, "tree." - agrifolia: many believe the printer made an error and that the name should have been aquifolia, “holly-leaved".

Found on CalFlora.net a wonderful site for native plant information and especially the stories and people behind the (Latin) scientific names of plants.

The proverb "from tiny acorns grow mighty oaks" seems so appropriate for this magnificent tree. The phrase does have a murky origin (Chaucer 1374, Thomas Fuller 1732 and D. Everett in 1797 - among others) Read more about this. The process of creating the next generation of oaks is accomplished in tried and true methods that appear to be left to chance. Pollen that is wind blown has to find a receptive female flower on another oak and a germinated flower creates an acorn that has to fall into a desirable location or be tucked away underground and forgotten. The acorn that sprouts and sends up a stem has to survive its leaves being eaten and competition for resources. Succeeding against the odds is what these graceful trees have been doing for a few million years!

More in-depth Information

The Oak-Fungi Connection

The more we learn about our world, the more it becomes apparent that all living things are connected. Most of us have learned the obvious: trees provide animals and insects with food, shelter and other resources and in return they spread seeds and pollinate flowers. However, oak trees are very dependent on a relationship that occurs underground, called mycorrhiza (plural: mycorrhizae). The roots of an oak tree provide nourishment for fungi living in the soil. In exchange the fungi provides minerals and moisture. This "mutual" relationship allows for both sides to succeed together. Mycorrhizal hyphae – tiny fibers extending from the fungal cells are comparable in function to the tree’s own root system. These fibers have more surface area for their size than the tree’s roots do. Increased surface area means that the tiny fibers can draw more water from the soil which also increases the rate of nutrient absorption. This process augments what the oak could do on its own with superior outcomes for both. Another benefit, the fungi can store and later share resources -- particularly phosphorus and nitrogen -- when the soil becomes depleted, which is important during times of drought or other stress. This is especially during the early portion of a tree’s life, when it is trying to establish itself in the habitat.

Fungi Information SourceFungi can be divided into three basic categories based on their relationship to their environment:

- Parasitic fungi that live off of living plants and animal tissue.

- Saprophytic fungi that live on dead wood, dead tissue of living trees, or dung.

- Mycorrhizal fungi that have a symbiotic or mutually beneficial relationship with the rootlets of other plants and are not limited to trees.

Scientists tell us that the fungi/root relationship began several hundred million years ago! As plants evolved, this relationship was key to their success. Ask a young student about photosynthesis and they will provide the basic details. Ask about the role that Mycorrhizal fungi play in the success of plants and most of us will have no clue, however, both processes are important to the success of plants.

"Great oaks take 300 years to grow, 300 years to stay, and 300 years to die." (Foresters' proverb, England)

Threats to Our Oaks

After surviving for millions of years, oaks in California are in serious decline. Population driven growth of cities, suburbs and exurbs are driving habitat loss. Drought, the spread of invasive species and an increased fire regime (pattern frequency & intensity) are factors that have lead to poor regeneration prospects. Oaks and desirable oak habitat have been cleared for housing construction and other land uses. When individual oaks are set aside, the trees chances for survival are challenged by: asphalt & concrete channeling water away from soil and are not always compatible with roots, e.g, driveways, sidewalks, parking lots, and streets. The community of plants surrounding the oaks changes along with the plant cover around them. Taking out shelter for acorns and seedlings changes above-ground microclimates, and likely disrupts relationships with other life forms. It is not just an oak tree - it is a world within a world - full of interdependent living forms. Well-meaning homeowners overwatering the trees (under the assumption that watering is good) often causing root rot in wet soil.

Fires have regularly occurred often enough in our wild-lands that our plants adapted strategies to survive and take advantage of them. The combination of invasive species, urbanization and drought have changed the fire regime from once every few decades towards much shorter periods of time. Seed banks can be depleted and or our outcompeted by invasives (many of which are more flammable). Fires impact on coastal sage scrub reduces the plant cover that oaks need when they are saplings.

Invasive plants are not the only threat facing oaks in our wild lands. Feral pigs/hogs/boars that have naturalized in California have become yet another invasive species. Most of us have no idea how many animals are out there in more rural areas. These animals have been especially devastating to oaks by unchecked foraging for acorns and truffles, insects and grubs that live in and around the oak's roots. Also on the menu for these feral hogs are oak seedlings.

In the past few decades as our climate has warmed and rainfall has wavered between years of drought broken by a season or two of exceptional rainfall, a variety of fungal infections have spread to vulnerable oaks: Foamy bark canker disease caused by Geosmithia pallida fungus is decimating Quercus agrifolia in Southern California. It is carried by western oak bark beetle into the xylem and phloem of the tree. This intrusion can kill a tree in few weeks to a year and is believed to be carried by wind blown rain - too little rain is bad and periods of intense rain are not that helpful either. Drought and a warming climate have put many of our oak trees under a tremendous amount of stress: which compromises their ability to fight disease. Trees all over the West are in extreme stress due to the very persistent droughts of the last couple of decades. Newer oaks are not replacing mature or fallen oaks in numbers that indicate a healthy turnover. Appearances are deceiving - lots of healthy mature trees, in the nurseries below them, future generations aren't surviving to produce the next generation of oaks.